Curated List

Top Mastectomy Tattoo Artists

David Allen specializes in botanical tattoos and pioneered mastectomy tattooing. Chicago Artist with MoMA recognition and gestalt mastery.

In Collaboration with David Allen

January 27, 2025

About the List

Delivering a mastectomy tattoo is just as much about listening and empathy as it is about understanding scarring and technique.

David has hand selected this list of artists who have the emotional and technical skills to perform mastectomy tattoos.

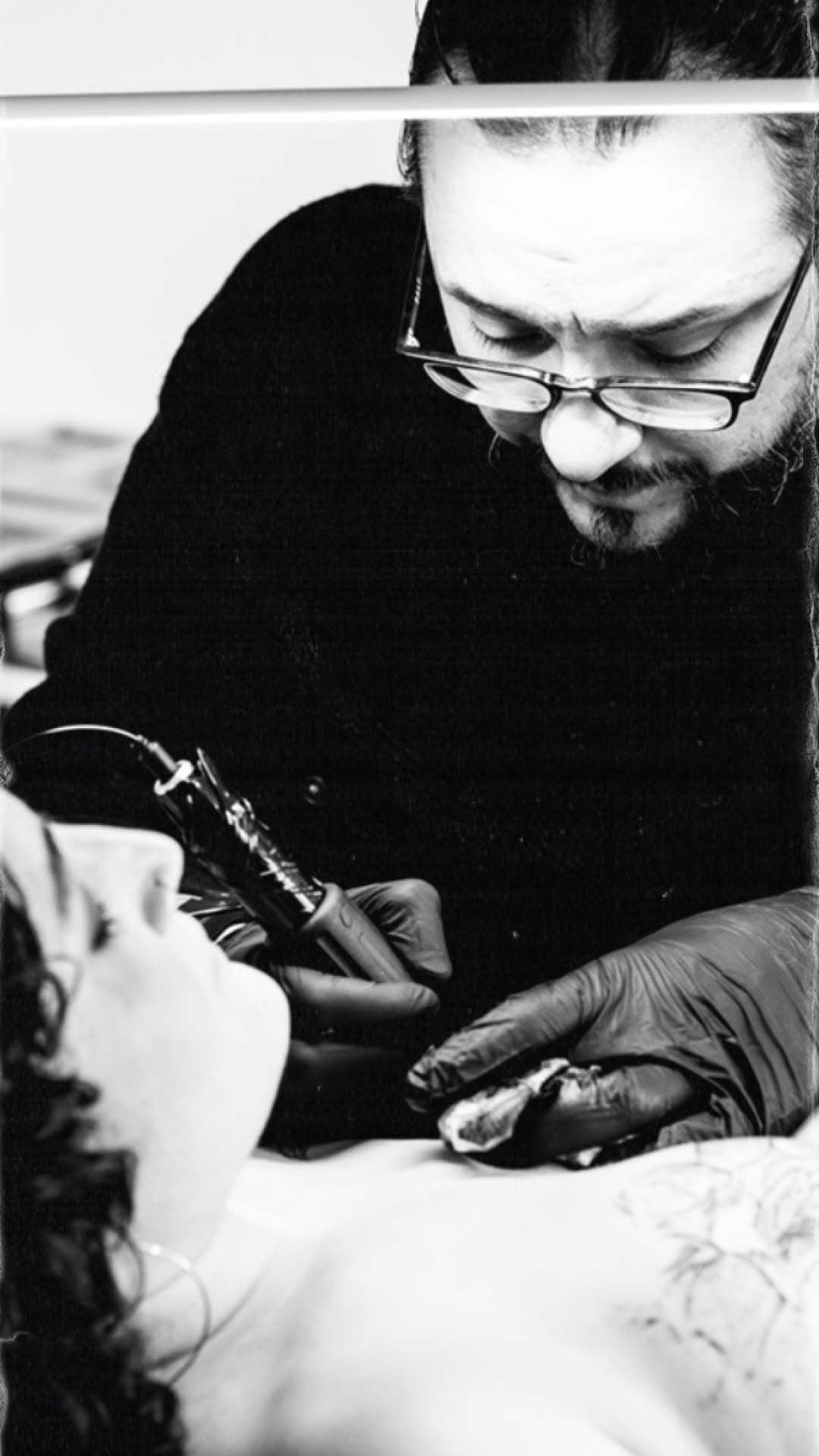

About David Allen

Chicago based, David Allen specializes in tattooing flowers, cacti, succulents and wildlife. He is also a pioneer in the field of mastectomy tattooing. He employs gestalt principles into his designs to deliver tattoos that effortlessly complement the contours of the body. David's tattoo work has been recognized by MoMA and JAMA.

Understanding Mastectomy Tattoos

The Pioneers

In the 1990’s, social activists started using art to raise awareness of breast cancer and women's suffering. In 1993, the New York Times journal featured a cover story that challenged dominant narratives of breasts, beauty, and the impact of breast cancer. The cover image was a self‐portrait of a one‐breasted activist, artist and photographer Joanne Matuschka. The image depicted Matuschka draped in a white cloth with her mastectomy scar exposed under the title, “Beauty Out of Damage.” This paved the way for a more open dialogue around breast cancer.

Marcia Rasner, who was diagnose with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy in the mid-80, and Pam Huntley are two women who opted for tattoos over reconstruction surgery.

“Getting my tattoo was the culmination of a three year dance with Breast Cancer. The tattoo changed my mastectomy scar into my shield.”

Pam Huntley

Inga Duncan Thornell got her tattoo after a double mastectomy in 1993. Madame Chinchilla and Mr. G, proprietors of Triangle Tattoo and Museum in Fort Bragg, CA, are artists who began performing early decorative mastectomy tattoos.

Techniques

Performing mastectomy tattoos requires specific skills– both emotional and technical. Artists performing mastectomy tattoos must be entirely present with the client in order to listen intently and show compassion. Mastectomy tattoos can carry significant weight and meaning that is hard to fully grasp for someone who has not experienced the trauma. Therefore, artists must be able to empathize as much as possible and translate emotion into meaningful art.

Further, artists must understand how to work with scared skin – which can be much more challenging to tattoo on. David, for example, will only work with women who are at least 6 months post-op so the scarred skin has some time to settle. Artists might even be required to speak with surgical doctors so must be knowledgeable of the skin.

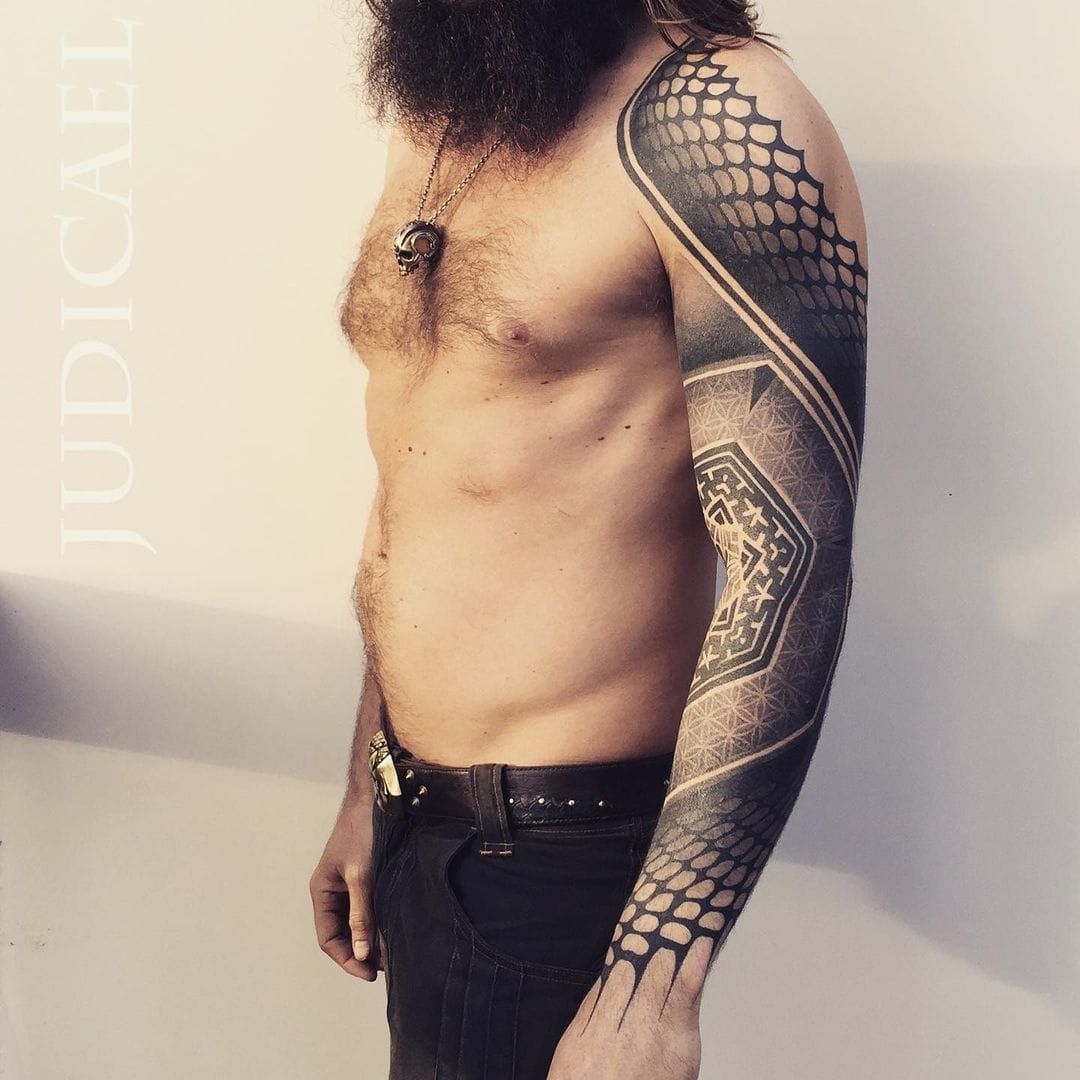

David Allen, for example, leverages gestalt principles, which are laws of human perception that describe how people group similar elements, recognize patterns and simplify complex images when we perceive objects. Tattoo artists may use the principles to design elements on the skin that are aesthetically pleasing and mask unwanted scars

Trends

To discuss trends in the area of mastectomy tattoos requires a broad consideration of societal and psychological norms. For many years, women who had undergone mastectomies would opt for reconstructive surgery of a breast and areola. However, reconstructive surgery is challenging, costly, and often requires multiple procedures. The result may differ significantly from the original breast or its twin. As a result, women started to actively refuse reconstruction – and tattoo over the scar tissue instead.

These tattoos range from recreated areolas ― which can be realistic-looking or take the form of flowers, hearts or other shapes ― to much larger, more expansive designs.

Artists such as David Allen took a decorative approach to covering scars, which was a departure from the normative recreation of the areola shape. For many women, by creating a new physical appearance, the tattoos represent the person they are after breast cancer versus recreating who they were before. This is a powerful statement by many women in taking control of their personal narrative instead of trying to erase what happened.

The Curated List

Brooklyn, New York

George Kalodimas

Manhattan, New York

Armandean Munoz

Los Angeles, California

Diamante Murru

Nevada City, California

Judicael Vales

Brooklyn, New York +1

Adriana Hallow

Dansville, New York

Pamela Carvalho

Bellmore, New York

Nicole Rizzuto

Brooklyn, New York +1

Ant the Elder

Chicago, Illinois

Manny Abadi

Pozzuoli, Italy

Moni Marino

New York, New York

Maxime Plescia-Buchi

Seattle, Washington

Victoria LoMonaco

Toronto, Canada

CJ C

New York, New York

Steph Tamez

Chicago, Illinois

David Allen

Brooklyn, New York

Gossamer Rozen

View the Full List

Follow David Allen

A trusted, Artist-led network of top tattoo Artists — a place where clients can search, discover, and book with the best.

Discover

Artists

Connect

© 2025 Gesso Labs, Inc.

Privacy PolicyTerms of ServiceReferral TermsGiveaway RulesArtist AddendumAI & LLM