Article

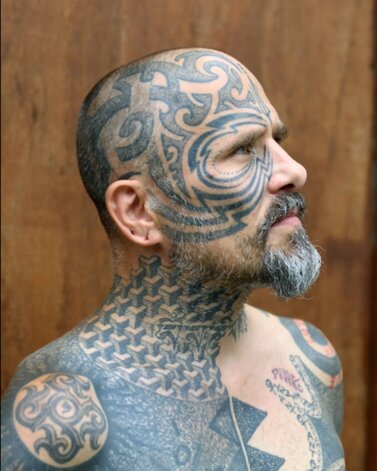

Tribal Tattoos and Influence

Explore the rich history and evolution of tribal tattoo styles, from traditional Polynesian, Māori, and Celtic designs to modern interpretations like neotribal, cybersigilism, and blackwork. Learn about the best tribal tattoo artists, techniques, and the cultural significance behind this enduring art form.

December 29, 2024

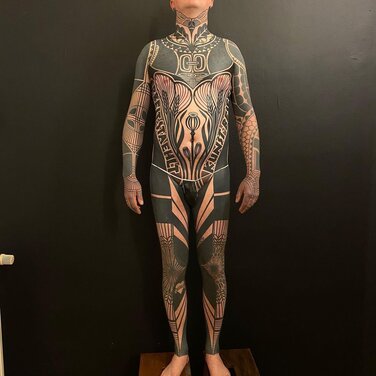

Tribal tattooing defies singular definition. The term as used today describes several different subgenres, and interpretations. It predominantly refers to the developments of a subgenre developed in the 1980s which borrowed from practices in Borneo, but removed from any true cultural symbolism. Spreading from the United States, inspired by Michigan-based Leo Zulueta, it quickly separated into two distinct currents: large-scale abstract work, also referred to as neotribal, later advanced in London with the likes of Xed Lehead, and spurred contemporary adjacencies inclusive of related blackwork, geometric tattooing, on one hand. And on the other hand, smaller ornamental motifs often looking like interlocking thorn-like structures. The latter eventually developing into today’s cybersigilism, combining technology and mysticism, and cyber tribal. In mass culture, a simplification of neotribal carries association to late ‘80s and ‘90s “tramp stamps,” applied to the tailbone, or bicep bands, among others. With Y2K nostalgia, we see some of this simplified tribal coming back into fashion too.

Simultaneously, another key current developed: western tattooists developing tattooing practices directly and literally inspired by “true” tribal.

True tribal, or truly indigenous tattoo practices from across the world, carries specific cultural significance. Polynesian, Celtic, indigenous Northwest Coast, Native American, African, and South American are examples. Accurate, symbolic tattooing that continues the traditions of Polynesian, including Māori, communities are primary examples of tribal styles and are practiced by non-western indigenous artists along with a few western artists who have deep knowledge of the symbolism and iconography.

Given the depth, and historical importance of tribal tattooing, this introductory article begins a series that will dive deeper into the variations of tribal.

The CO:CREATE Method

Every tattoo style has a range of expressions. At CO:CREATE, we acknowledged that range, and are focused on three core considerations for describing the tattoo you want: aesthetic, iconography, and technique.

Aesthetic refers to how the tattoo looks. Line weight, color, saturation, movement with the body all contribute to look.

Iconography examines the meaning attached to the tattoo. We describe the cultural, historical, and spiritual connections chosen imagery carries and communicates.

Technique specifies the methods used to. For example, different techniques of shading (whip, dot, drag, etc.) create different levels of depth and dimension. Color layering, color packing, or distinct forms of linework, all contribute to refining the final form of your tattoo.

Discussing these three elements with your artist helps assure you get your dream tattoo.

Tribal Tattoo Iconographic Sources

Post-Zulueta ornamental tribal is often rooted in a revival of 70’s to 90’s culture. As such, its iconography is meant to evoke more or less romanticized aspects of that era. Mostly centered around early American Pop-culture. While the “neo tribal” branch often inspires itself from futuristic or retro-futuristic outfits, as well as optical or psychedelic art.

On the “true tribal” side, Polynesian motifs representing human form (Enata), the sky, niho mana, the spear, the ocean combine to form patterns that are commonly associated with tribal tattooing — especially in connection to Māori, Samoan and Hawaiian

Tribal Tattoo Aesthetics

All of the tribal currents have in common to predominantly rely on solid graphic surfaces, often black or shades of gray. There can be dense lines, intricate patterns, subtle dotwork and subtle gradient shading. The introduction of color (for example, red or chrome) as contrast is also prevalent in the ‘80s and ‘90s subversions of tribal.

Tribal Techniques

Technique, like the history of tribal tattooing itself, is broad and varied. True tribal, linked to historic practice, relies on hand tapping, with a team of people stretching skin, is an ancient technique. The resurgence of practitioners fully honoring and spreading cultural traditions has continued this and other ancient techniques (you may witness at certain conventions). Modern tribal focuses on machine work, bold lines, dot shading, and diluted black (gray scale) shading.

Contemporary Tribal History

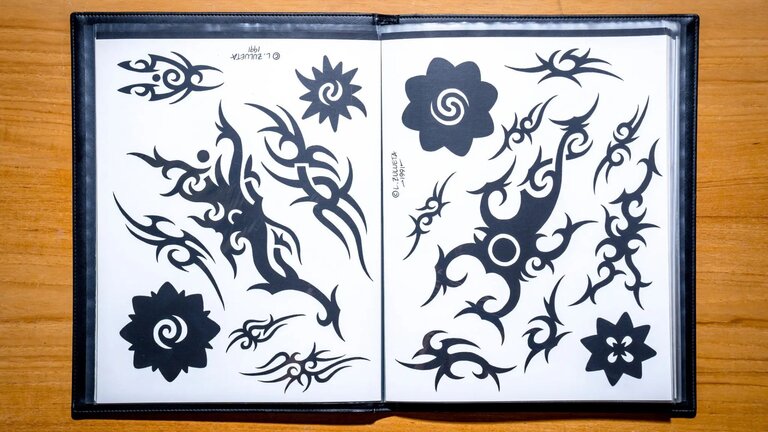

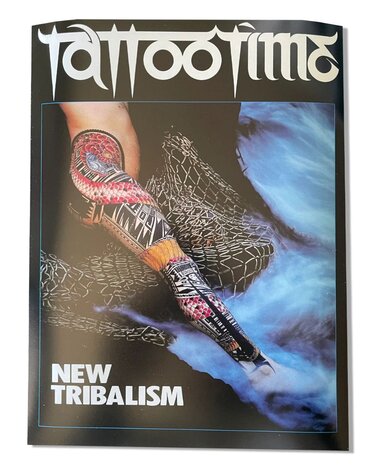

Contemporary tribal tattooing has origins in the late 1970s. Don Ed Hardy's issue of Tattoo Time from 1982 "New Tribalism" documented the history, spanning centuries, of indigenous practice throughout the Pacific Rim and positioned tribal tattooing as one of the major categories of tattooing alongside traditional, Japanese, and fine line/black and gray. Designs from Borneo, Samoa, and Fiji inspired Leo Zulueta, who began his career in 1981, to develop his own vernacular. Known as the "father of modern tribal tattooing," Zulueta helped to popularize this (new/neo) approach to tribal tattooing, which removed spiritual context, from his famed studio, Spiral Tattoo. Eventually, this version of tribal was watered down to the small scale popularized by celebrities. “Tramp stamps,” bicep bands, and adornments to floral arrangements recontextualized tribal in several subgenres of tattooing. Fineline and the new school both began to incorporate abstract tribal patterns, aiding in popularizing the term. Prominent flash of the era representation is found in the likes of Cherry Creek.

Xed Lehead

Simultaneously, as tribal aesthetics were recontextualized throughout the tattoo industry, Zulueta’s large-scale approach built steam in Los Angeles and London. In 1989, the publication Modern Primitives investigated the trend, situated alongside newly popular piercing practices, and in the 1990s London-based Alex Binnie, from his IntoYou studio, progressed and engaged a new generation of tribal-inspired artists: Xed Lehead, Tomas Tomas, Andreas 'Curly' Moore, and others. They, in turn, inspire people now associated with geometric tattooing — think Thomas Hooper and Jondix. Western artists like Chris Higgins honor indigenous ritual with faithful study and composition of Māori tattoos. In contrast, Black Symmetry evolves neo-tribal through engagement with psychedelic patterning, while Gerhard Wiesbeck draws from electronic circuits to develop his patterns. Cybersigilism, cyber tribal, and techno-tribal, all combining mysticism and cyber aesthetics, are among the latest aesthetic advances that owe greatly to neo-tribal tattoo influences.

Future articles will cover Polynesian, Celtic, Native American, cybersigilism, blackwork, and cyber tribal in more detail.

Tomas Tomas

Artists Steph Tamez, Oscar Conejeros, and Black Symmetry represent the range tribal style. Explore their work and more artists that are at the forefront of continuing indigenous tattoo practice on CO:CREATE here.

Discover

Artists

Connect

© 2025 Gesso Labs, Inc.

Privacy PolicyTerms of ServiceReferral TermsGiveaway RulesArtist AddendumAI & LLM